Tally to Binary: Understanding Data for Better Development

Introduction

To write good software, you need a solid grip on data.

Every video you watch, every song you listen to, every message you read — they all feel different on the surface. But inside your device, they’re the same thing: binary, just 0s and 1s making everything come alive.

This is a gentle walk from ancient counting to the heart of modern machines. No heavy theory, just the thread that ties it all together.

Let’s start where counting began.

A Brief History of Counting: From Tally Marks to Binary

Imagine a shepherd at dusk. One sheep, one stone in the pouch. Two sheep, two stones. Counting was touch, memory, and trust.

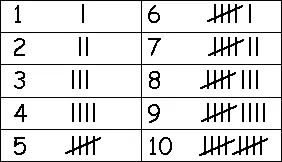

Soon, people carved tally marks instead: four lines for four apples—||||. At five, a diagonal slash grouped them. Cave walls, bones, wood—whatever held a scratch.

Now imagine counting to a million. Weeks of lines. A forest of scratches. Impossible to read, impossible to share.

So we shrank the world of counting into symbols and signs.

The Decimal System (Base 10)

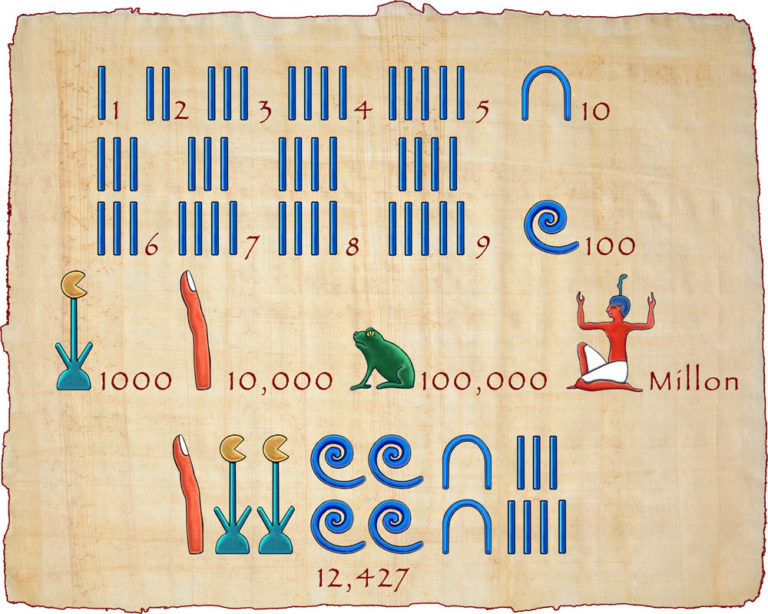

Early symbols tried to help. Egyptians used a coiled rope for 100, a lotus for 1,000.

But unique symbols for every number? Chaos.

The breakthrough: reuse digits by position.

Enter base 10—ten symbols (0–9), each place a power of ten.

Rightmost digit: ×10⁰. Next: ×10¹. And so on.

Let’s see it in action with 319:

| Digit | 3 | 1 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place | 10² | 10¹ | 10⁰ |

| Value | 3×100 | 1×10 | 9×1 |

→ 300 + 10 + 9 = 319

Same trick works with any base.

The base just changes the rhythm.

And computers? They dance to the beat of two.

Binary (Base 2): The Machine’s Native Tongue

Why two? Because hardware is honest.

At the switch level, a transistor is either conducting or not. Using two well‑separated voltage ranges (low and high) gives strong noise margins, making circuits faster, cheaper, and more reliable. More than two states are possible in theory, but they are harder to separate, more error‑prone, and waste more power—so base 2 wins in practice.

A transistor is a switch: on or off.

A hard drive magnetizes a spot: north or south.

A Wi-Fi signal peaks or dips.

A pixel glows red, green, blue—at different strengths.

All of it: 0 or 1.

That simplicity scales. Billions of switches breathe in unison, and from that rhythm, apps, games, and cat videos emerge.

- Storage: Patterns etched in silicon or spinning disks.

- Audio: Waveforms sampled into numbers, then back to sound.

- Wireless: 0s and 1s riding invisible waves.

- Images: Millions of pixels, each a mix of red, green, blue.

Binary isn’t just low-level—it’s universal.

From Bits to What We See

Binary strings get long. So we compress again.

Hex: Shorthand for Bytes

- 1 bit = 0 or 1

- 1 byte = 8 bits

- 1 hex digit = 4 bits

→ 2 hex digits = 1 byte

So 0x41 = 01000001 in binary = one byte.

Text: From Codes to Characters

- ASCII gave early English 128 characters.

A= 65 =0x41. - Unicode gave every script a number (a code point).

A= U+0041. - UTF-8 packs those code points into 1–4 bytes—so the world’s writing fits in files.

Same A? Still 0x41 in UTF-8. Backward compatible. Smart.

Color: 24 Bits of Magic

Each pixel often gets 24 bits:

8 for red, 8 for green, 8 for blue.

2⁸ = 256 levels per channel

→ 256 × 256 × 256 = 16,777,216 colors

That’s why your screen feels alive.

Conclusion

- We began with stones and scratches.

- Place value let us reuse digits—first in base 10, then base 2.

- Hardware speaks binary because it must: on or off, nothing in between.

- Storage, sound, images, and networks follow the same pattern.

- We compact with hex, encode text with UTF-8, paint with 24-bit color.

- A single byte like

0x41becomes theAyou just read.

The journey from tally mark to pixel is one of compression, reuse, and translation.

Next time, we’ll put it into practice:

reading binary files, decoding UTF-8 by hand, building a tiny image from scratch—all in simple, runnable snippets.

If this sparked curiosity, stick around. The fun is just beginning.

Thanks for reading. See you in the next one.